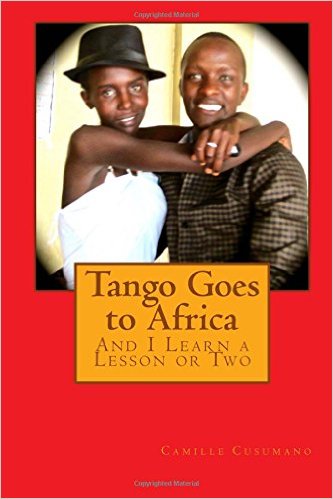

A few years ago I received an email from Camille Cusumano requesting support for her “Go Fund Me” campaign to teach tango in Africa. Camille is someone I’ve known for several years now, first as the author of Tango: An Argentine Love Story and then in person as a Bay Area dancer and teacher. Her teaching partner in this endeavor was Mungai Waweru a young Kenyan-American who was quickly becoming an accomplished tango dancer here in the Bay Area. Inspired and intrigued by this request and their mission, I was also very curious to learn of how it would transpire. Would it work? Would young Africans even want to learn Tango? Recently I had the opportunity to read Camille’s story of the experience. It was far more intriguing and inspiring than I imagined. Camille has graciously shared an excerpt from her recently published book Tango Fantasia.

Tango Goes to Africa (Excerpted from Tango Fantasia)

Tango Goes to Africa (Excerpted from Tango Fantasia)

By Camille Cusumano

In late February, 2014, Mungai Waweru and I flew to Nairobi Kenya to teach slum-dwelling youth Argentine tango. I had been invited by a Christian church group two years before and finally got the time and finances to be able to jumpstart this project. The goal was to get the kids, ranging in age from about 17 to 29, skilled enough to eventually teach tango and earn some income.

Mungai and I taught about fifty youth at two different venues, both church halls. The main one was St. Peter Claver in the grungiest part of Nairobi. (Peter Claver was a Spanish Renaissance man, who became the patron saint of slaves.) We taught there Mondays through Thursdays, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. The floor was large enough but decomposing stone and unmaintained. We had to sweep up the decay and debris constantly. When it rained, the water poured in through holes. The afternoon wind carried the street stench. We got used to it only after four weeks.

The youth were instantly delightful to work with. Present, engaged, eager to learn, accepting of critiques, willing to practice, passionate about the dance, so affectionate and open toward Mungai and me. The teaching was a joy. They were shy at first but then began to show their many talents. At the end of the long exhausting day, they’d perform a skit for each other. One time, Koresha, Jack, and Alex shouting vehemently in Swahili, were channeling their powerlessness, it seemed, into a satirical skit about a slumlord taunting tenants. Jack was on all fours pretending to be a table. It was in Swahili. Mungai and I only laughed because of the infectious nature of laughter. There were several accomplished salsa dancers. I put on my favorite salsa tune, Lobo Domesticado, and they gave us a riveting display of that spicy Latin dance. Amazing that the healing power of art is still untapped.

Having been a student and/or teacher of tango going on twelve years now, I can assert one thing with great certitude—that no two people teach tango the same way. It is exactly like the elephant that the three blind men keep trying to describe to each other. One starts at the trunk, one at the tusk, another at its tail. So after one or two days of teaching our classes of about fifty kids all told, Mungai and I disagreed on one method he used to teach the youth how to shift weight. I thought it was a mechanical gimmick that confused them. But Mungai, who adored Gabriel Misse, the Argentine teacher who used this mechanism, was adamant that it was useful.

After one heated debate, I conceded to his preference. After all, he was closer in age to the youth and resembled them more than I, had a good strong voice for teaching, had an organized idea of the sequence of teaching, and he would be with the students longer—I’d leave in April, he in July [Note: Mungai ended up staying a full year].

I don’t think I’m exaggerating to call Mungai a prodigy when it comes to tango. After a mere two years, he’s smoother, more polished, musical, and sensitive to the intricacies of the dance than many longtime tangueros. I think he has an innate ability to feel the dance internally. His honed skills in hiphop and as a flight instructor for indoor skydiving no doubt help him be such a top-notch leader. I speak from a place of having danced with hundreds, if not thousands, of leaders through my years of living in Buenos Aires and dancing in major cities from San Francisco to New York, Denver to New Orleans, Baltimore to Philadelphia, and Paris to Prague. Oh, let’s not forget Nairobi. It takes a lifetime-and-a-half to learn tango, the Argentines say. But Mungai is the exception who proves the rule.

The first day of teaching at St. Peter’s, I told Mungai, “Indulge me, even if you think it’s corny.” First, I reminded the class that the night before, their compatriot, Lupita Nyong’o, had won the Oscar for best-supporting actress and had given a stirring acceptance speech. Then I put on Peace Train by the O’Jays and had us all hold hands in a big circle of friendship, and march around to the music. I can still see the obliging youth now, a kaleidoscope of colorful and funky clothing and the shoes—the green high tops, beaded sandals, purple plastic loafers—as we snaked into one tight group hug bouncing together to the music. The ritual set the tone and if there was any ice, it was broken and melted. The number of hugs we all shared in a day far exceeded the minimal daily requirement set by the experts.

Teaching Tango—in Africa? “As soon as one starts digging into the origins of the tango, its black creole roots emerge,” writes Robert Farris Thompson in his book, Tango, an Art History of Love. Tango? In Africa? How many times was I asked that question. The fact is, that tango traces a direct genealogy to Africa. Yale professor Thompson, with significant research, makes that convincing and cogent argument in his book.

Thompson writes, “Tango culture and tango humanism are Buenos Aires phenomena. They emerged from the encounter of dance concepts from Kongo with the city’s cultural and social situation, involving African-born blacks, blacks born in Argentina, European migrants from Spain and Italy come to . . . seek . . . fortune . . . also of Andalusian influenced gauchos who brought stamping patterns . . . the habanera arrived with black Cuban sailors, . . . . Elements came together in late-19thcentury Buenos Aires. But the strongest root is pure Afro-Argentine, a development of Kongo-style dancing, as elaborated in black dancing groups called candombes . . .” Of course, even our Kenyan students didn’t know this history.

We started with teaching the kids to walk—how to step across body in a straight line, with good posture, landing on the balls of the feet. We broke down the mechanics. We showed them how to shift weight, the proper way to execute an extension and how to transfer weight. We taught them rock steps, check steps, and pivots, and how to perform contra-body movement or spirals. We showed them the unique and dynamic embrace of tango that is ever shifting, never fixed (as in ballroom or American tango). We slowly introduced them to the basic steps of tango— walking in cross and normal systems, front and back ochos, molinetes (or giros), the cruzada or cross. Mungai was fond of explaining what I call the “taxonomy of tango”— the four ways the body can move: front cross, back cross, open step, pivot.

I don’t think the students always understood the words, but they watched intently and showed they understood the body moves. I liked Mungai’s passion for the dance and the gentle way he led—most beginners overdo it at first—and that he was an equally good follower. It is no surprise that by the time I left Mungai to teach alone—on April 3—our kids were dancing to tango, vals, and milonga music. And a good crop of them were the crème de la crème, picking up such advanced moves as leg wraps, enganches, lapices, and boleos. The teaching was rigorous as well as rewarding. It was unlike what I’ve experienced with any other population (adults and seniors) I’ve taught.